DAVID IRELAND

“YOU CAN’T MAKE ART BY MAKING ART”

by Camile Messerley

The David Ireland House at 500 Capp Street, SF featured in Days No.3

Climbing up two flights up rickety stairs from my back door to the roof since moving to my home has become a part of my morning. As I walk, motion-sensored bulbs switch on, illuminating each neighboring apartment through a twin window facing the steps. I look through to long quiet halls, white walls, and wood floors blushing empty inside each. Careful not to rock the boards beneath me or spill my tea. Lately, I’ve been climbing up to the roof at The David Ireland House, where I work as an Artist Guide. The late Bay Area maker, mentor, and explorer David Ireland lived inside his greatest sculptural work for over three decades. Today, the home is a compass to us as we develop exhibitions and educational programs and work with collaborators to nurture our part of the Bay Area’s cultural community. Our current artist in residence, David Wilson, spends a part of his day up there drawing. Asked recently to assist and collaborate with documentation of his time and work, I began by recording the process of him building a single-seat bench to sit on the apex of the roof’s slope. In between hand saws and measure, we could see neighbors on their roof holding a yoga class in the noontime sun, later the mission mobile food distribution.

Whether asked or not, over the past year, I have been documenting in the house. Before the house closed last March, I spent every free afternoon sitting with Alex Ehmer as she polished the copper window for two weeks. Ehmer is the current lead artist guide and a close friend of mine. Documenting this process was a personal endeavor that I wanted to witness and remember with her. The copper window did not get polished since long before Ireland’s passing in 2009. In a 2001 Interview Ireland shared that he “used to religiously have a little ceremony where I took the film off it to make it a bright piece of copper, and since I’ve lived with it all these years, just letting it take its natural course, then it makes me want to leave it alone.”

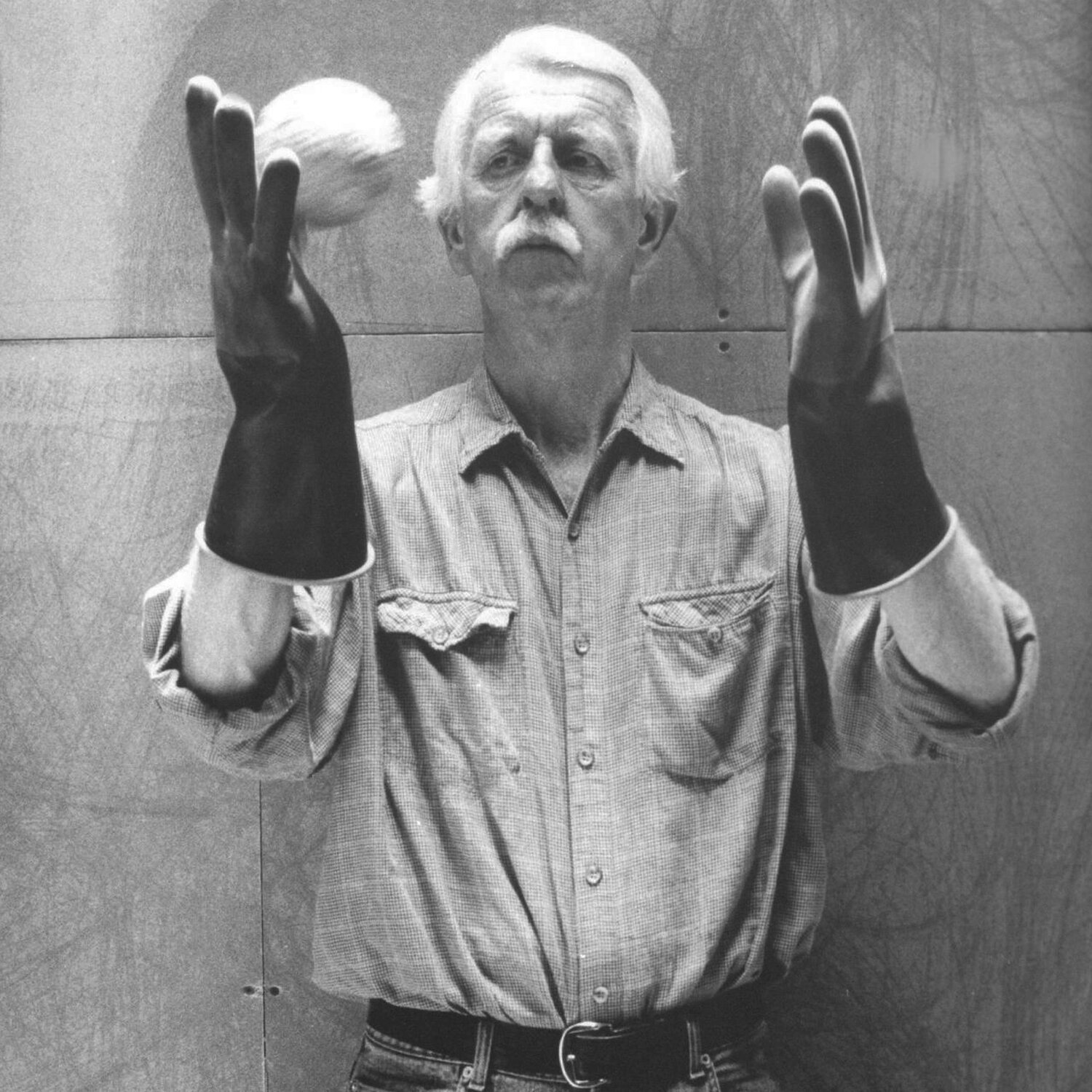

David Ireland, Dumbball Action, 1986

David Ireland, Exhibition Poster, 1980

The origin story of the copper window I learned first is that Ireland came upstairs to the parlor room and found a rock on the floor and a broken window above. Rather than adding a new glass window, he inserted a massive copper sheet to permanently etch in the San Francisco skyline view at the time. When guests view this today, we pause our story to play an accompanying cassette tape below that describes that view at an auctioneer’s pace. Ireland wanted something that communicated the inside and the outside. He chose copper for its relation to printmaking but also as a conductive element. When shined, it became something else. As early as 4000 and 2000 BCE, Mesopotamians and Egyptians polished copper to create mirrors. These were known as sacred and often divinatory tools to hide an image. Mirrors are also in feng shui utilized to shift energy. Ireland’s choice to use this etching material, though, is more closely related to printmaking. By introducing it to a window, he moves the context. This kind of decision was intuitive to his practice and reflects what fellow Bay Area artist John Roloff refers to as organic logic.

An intrinsic facet of how artists like Ireland approach their studios with an organic logic, Roloff defined this as “embrace[ing] complex, systemic, intuitive and process-oriented aesthetics and methodologies,” and relates to site-specific relationships. Responding intuitively to the entire house Ireland moved into in late 1975, by ‘entire’, I also mean ‘full’. I am referring to the inanimate inhabitants and the 95-year-old man he met in his bedroom upon arrival. Countless jars, stacks of newspapers, a broom in every corner, these became his materials. From 1975-78 performed a series of maintenance actions. Each was an act of care that released and preserved a remnant in the house’s history. Remnant’s included patties of wallpaper thrown up on the now glowing polyurethane-coated walls that Ireland would call art fuel, tossed into the fire when they fell— or the dust swept into a jar each morning after sweeping the stoop. Many of these actions we carry on, we still sweep each morning. In a more controlled way, we even open up the house to let neighbors and passers-by explore though they can no longer have their lunch in the kitchen and root through the drawers as David once allowed by leaving the doors open wide. Our repetition in this practice feeds the intergenerational collaboration with the house that David also felt a part of. Over the last several years, the house has seen multiple exoduses.’ In addition to the persistence of concrete and polyurethane, I see the degree to which the place is alive and well being dependent on our friends. Not just of David’s but now of mine and my colleagues and peers amongst the staff.

Living room: Leather chairs, chandelier deconstructed television all by David Ireland

Our homes nestle us in their mystery of personality. As we breathe life into them and clear the collecting dust, we release particles of their history, like picking a patch of paint to find a patch of paisley or lifting a floorboard to excavate a hidden staircase. For Ireland, this became intrinsic in his practice of the art of daily life. Today the home continues to be a generative portal to its inhabitants, caregivers, and surrounding community. As we care for it, our eyes cross corners previously unnoticed like a strip of film sunbleached in a back window blind. As artist guides, we will tell you the story of how Ireland came to the house, what he did here, make you dinner or sit and have tea. Many of us are also friends. Something that cannot be understated in this home’s importance is the idea that we all get by with a little bit of help from our friends. We are known as artist guides because of the dexterity of knowledge relating to craft and artist practice that we bring to the home. Depending on the day and guide, you will have a slightly different experience and conversation.

Being unable to host guests during the pandemic, we have had to tumble down other avenues. As individual artists, editors, organizers, printmakers, filmmakers, and writers alike, we spoke with old friends of David’s and conducted independent research, and formulated new programming practices. Our interpretive role has also shifted to be one of deep diving reflection. Reflection as an activity while in the house is constant. There is a piece that I’m currently on the hunt to locate. Ironically, it is called In Search of the Perfect Mirror. No one quite knows what it looks like or where it lives in the archive yet. The work came up in a lecture Ireland gave at SCI-Arc in 1991. He didn’t show the piece from his collection of all of his thousands of slides. For now, I’m content with the idea that maybe it wasn’t a physical piece but meditation or another process he considered from time to time.

The David Ireland House at 500 Capp Street, SF featured in Days No.3

Alex and I had been sitting quietly for some time. It was one of those early spring afternoons when the sun’s heat started to cook the fumes of Brasso and Bon Ami. I sat on the floor and rested my eyes a minute. The open windows let in a breeze that rustled the plastic sheathing covering the room’s inanimate inhabitants. The pile of Brasso bluegreen-soaked cotton balls piling up taller and taller around Alex on the floor. She had gotten beyond most of the grime. Over and over again, I’d hear her say, “so dirty, so dirty soooooooo—” Just then, I opened my eyes, and sudden strobe broke out, on and off, on and off. The fluorescent light tubes between the pocket door arch behind her, and she could see herself clearer than before. In her reflection, I joined her, standing between us, another figure joined us. Their hands moved closer, each making wide arm-casting broad circular movements. Alex and the mirror model started moving in sync as if we were in the Karate Kid. Brushing swifter figure eights, watching closely, I reached my arms up to join. Soon the room had flooded with light. It was as if the moon were a bathed penny reflecting another side. The gloves she wore began to tear, and as the tape below began to play, or did it? The cassette wasn’t the same auctioneer reeling off the view that once was behind the copper window. The tape asked us to lift the window pane, climb through. Alex and I looked at each other and then to the window. Its latch swung open. Together we raised the pane. The window weights began to sing. It felt as though we had walked through a hot plate of jello. The room was slightly vibrating, glowing as if just lacquered. I wondered there was a sun inside the room with us? Like a sunset, the glow shifted to a midnight blue, moments later, institutional green, then red, then back to the rich amber glow. Transfixed, we hadn’t yet realized the dance around us. Familiar faces turned, and leaped, and spun, and dipped, and tapped, and soon we were too.

Find more information on David Ireland and 500 Capp Street here.