DAVID KRAMER INTERVIEW

“I did a show in Toronto I called ‘Handmade Memes and Analog Tweets’. The dealer asked me what an analog tweet was. I told her ‘It’s when you yell out the window!’”

David’s studio, Williamsburg, Brooklyn 2020

It seems like David Kramer has been with us forever. His work is at once universal, direct, and clear yet it touches something deep and eternal. Is it the human condition, the American condition or a New York state of mind? Maybe all of it. We crave for more and more of his wit to find out. “I have nostalgia for the things I have never known” reads a shirt he created for Hedi Slimane’s groundbreaking Summer 2020 Celine show. We argue that we do know these things as they have always been with us deep inside. And now more than ever, we need someone with a healthy dose of cynicism to draw them out.

Days: You work in Brooklyn. Can you tell us a little about your background and if your location plays a role in your work? Also, could you give us an idea about your world, and what is your day like?

David Kramer: I live in Manhattan and work out of a studio in Williamsburg, Brooklyn. I’ve had the same studio there for almost 18 years. The neighborhood has changed so much I often joke “... I am the last artist working in Williamsburg.”

I was actually born in Manhattan and have spent most of my life living within 30/40 minutes from where I first lived. We had moved to the suburbs when I was just about 4 years old (New Rochelle, NY) and I spent my entire childhood complaining to my parents who both commuted to NYC everyday, that it was totally unfair that they got to go to the City and I was stuck in the suburbs. I grew up imagining a life in NY and when I could, I ran to live there. It was back in the 1980’s and the City was something of a disaster but I loved it so much, and I really began then to make art about the contradiction between what I wanted and expected, and what l really got out of life. I think this is sort of the theme underlying in my work still to this day.

Copious Reassurance, 2018

D: Can you tell us briefly about your ‘calling’ as an artist, and give us a little background on yourself?

D.K.: When I was a kid, I was always super into drawing and block building etc. I was a terrible student. I am totally dyslexic and can’t spell. I had a hard time in school and constantly spaced out and drew in my notebooks in class.My parents were the first in their families to go to college. My dad was super smart. He went to a tough high school in Brooklyn and somehow got into Warton Business school and Harvard Law School. The last thing he wanted was his dumb kid going to art school. Honestly, I tried super hard to follow his footsteps but even in college I was doodling in my notebooks and I just loved the art classes I was taking.

At some point in my Junior year at school, I realized that when I thought about the rest of my life, I had no choice but to try to be an artist. I had to go through total hell from my parents and it was really quite difficult. I love making stuff. I just love the process of building something or painting or trying to make an accurate drawing of what I am looking at. But for me the hardest part at least when I was just starting out, was figuring out what to say. Subject matter always loomed as the Holy Grail. It still does. Eventually, I would make paintings and just keep painting away until the title or a sentence would jump out of it. Usually it was some kind of description of the process, or a joke about the person making the piece. I figured out how to find subject matter through process... Then I would write the subject across the painting and that usually is how I knew the piece was finished.

D: There is a lineage of American conceptual artists such as Jenny Holzer, Barbara Krueger, Bruce Nauman, etc. How much are they an influence in your work and do your see yourself evolving the approach?

D.K.: I always found more connection with the West Coast conceptualists. I just loved the work I saw coming from California and even Vancouver, and felt that was perhaps the dialogue I was having even though I was talking with a New York accent. Nauman is great and I definitely remember seeing back in Leo Castelli Gallery, the show with the Clown holding the goldfish bowl to the ceiling or taking a shit and being blown away. But for my money on a regular basis, I am moved by John Baldessari and Jim Shaw, and Rodney Graham and Ed Ruscha. Those are the guys who I really feel like I am talking to.

David Kramer featured in Days No.2, Winter 2020

D: :I can see an almost romantic ambiguity of innocence and longing for a deeper truth in your work, that is colliding with our current world of confused politics, personal values and intimate belonging. Can you speak more about this?

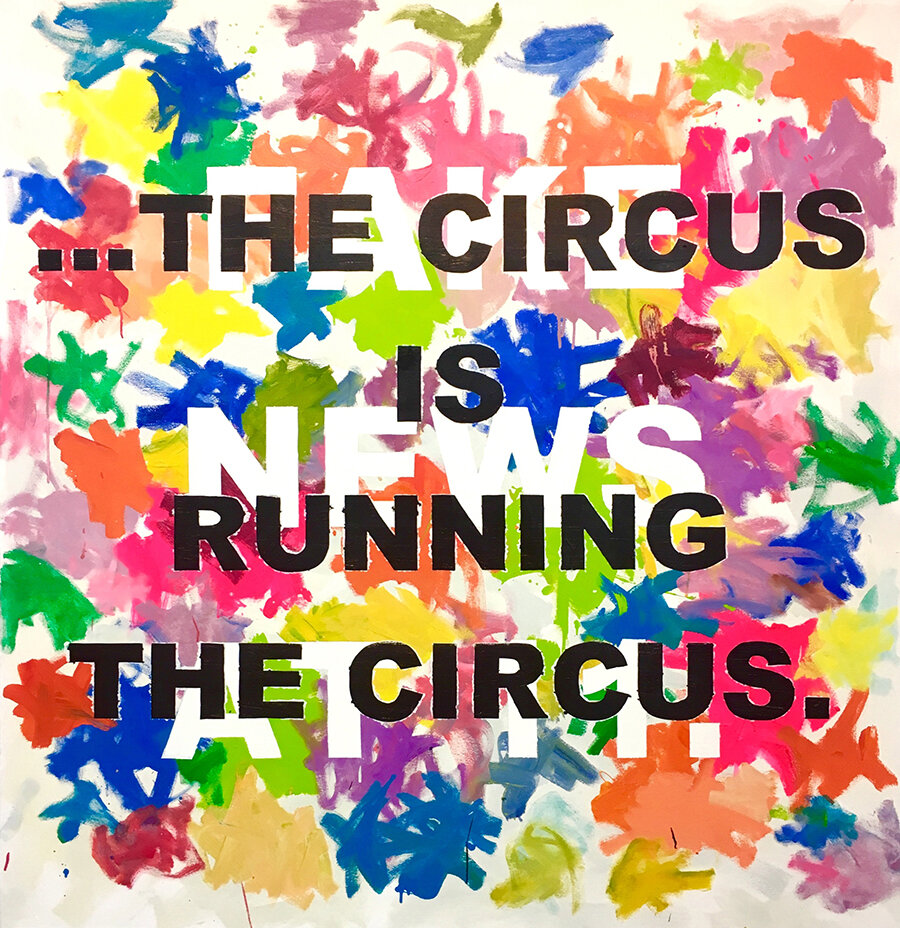

D.K.: Yes, well, that is sort of where Jenny Holzer and Barbara Krueger and I really differ I think. They seem to present their work as finished fabricated products of their ideas. I feel like I am mucking about trying to find my ideas. The process ends up as part of the end result. But like them, I am totally interested in politics and advertising and the way politicians are like admen pitching lies and false sentiments while trying to sell you something. I love the way those kind of big bold untruths look as art. The irony and humor is delicious all be it toxic in the real world of politics.

D: How does technology as a medium or tool fit into your autonomy as an artist? Particularly given a less physical world in which art would be presented?

D.K.: Well in terms of my work as an artist /self promoter, - yes. I am thinking of how much my work started to change when I was say blogging and then using Facebook and now Instagram. The speed that people can see my work now is fantastic and has made my dialogue so much more important and maybe better. It is funny because my work always seemed to have been like a meme even before I knew what they were and now I say that I am making “Handmade Memes.” I did a show in Toronto I called ‘Handmade Memes and Analog Tweets’. The dealer (the late Katharine Mulherin) asked me what an analog tweet was. I remember I told her “It’s when you yell out the window!”

D: What things in your world, beliefs or biography find themselves into your pieces, or where is the threshold between personal and public statements for you?

D.K.: Honestly much of my work, my words are completely personal. They really come from me talking to myself. I am very critical and self deprecating. But when the words seem to work best is when they somehow come off as universalities. It is often funny to me how many people can actually identify.

David Kramer & Celine S/S’20

D: Are there any other influences or inspirations that are part of your process?

D.K.: When I was in art school, a professor asked me who were my influences. This was in the 1980’s and at that time I said Woody Allen. I just loved the banter and the self reflection in the jokes in films like Manhattan or Annie Hall or Hannah and Her Sisters. I know it is probably going to get me canceled but I still think that period of his work really spoke directly to me about the value of conversations to New Yorkers and our daily urban existence. I think the hardest part about the COVID-19 shutdown has been the loss of the casual conversation on a subway or on a street corner. Running into friends. That is what defined NYC to me and honestly it is this type of socializing that filled in for my sad excuse for a social life, and also seemed to be a fantastic source for jokes or ideas to write down and think about later.

D: What project are you most proud of or what part of your work this far has been most rewarding?

D.K.: I like to say the best part about being an artist is when you are in the middle of everything. I love it. Having a show is ok but it is the buildup that is the best part. Like I said, I live to get lost in the process.

D: What is next for you?

D.K.: I have a show of my Hook Rugs coming up at Freight and Volume Gallery in NYC mid October called ‘Mar-A-Lago Sunsets’, I hope we make it to October and back... That’s all I can say at this point!

Clown Painting, 2019